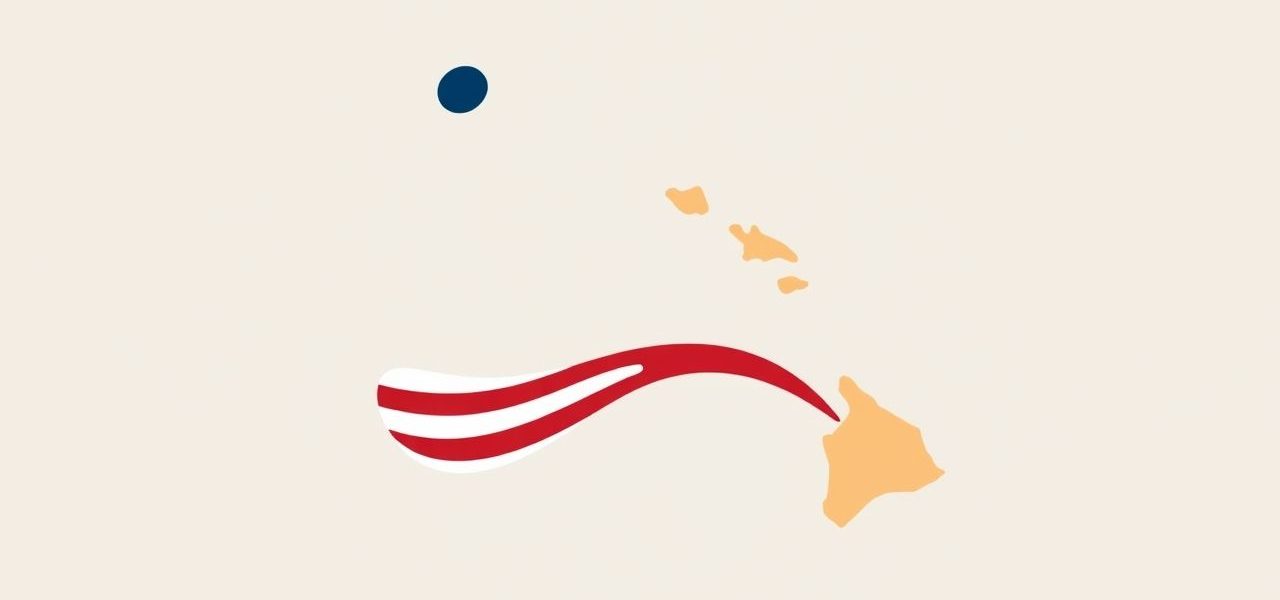

The American annexation of Hawaii marks one of the most significant turning points in United States expansionism and Pacific geopolitics. The islands, once an independent kingdom with its own monarchy and thriving economy, were gradually drawn into the orbit of American influence due to political maneuvering, military strategy, and economic interests. Understanding the events leading up to the annexation, and the aftermath that followed, provides important insights into colonial ambition, indigenous resistance, and the evolution of American imperialism in the late 19th century.

Early American Interests in Hawaii

Before annexation, Hawaii was an independent kingdom governed by a line of monarchs beginning with King Kamehameha I. The Hawaiian Islands attracted increasing attention from foreign nations, particularly the United States, due to their strategic location in the Pacific Ocean. By the early 1800s, American missionaries had established schools, churches, and communities in Hawaii, often influencing local governance and culture.

American businessmen, especially sugar planters, grew wealthy and powerful in the islands. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 between the U.S. and the Hawaiian Kingdom gave American producers the ability to export sugar to the United States duty-free. This solidified the economic relationship between the two nations and increased U.S. involvement in Hawaiian affairs.

The Bayonet Constitution and Political Upheaval

In 1887, American and European residents forced King KalÄkaua to sign what became known as the Bayonet Constitution. This document significantly reduced the power of the Hawaiian monarchy and gave more political authority to foreign landowners and elites. Voting rights were restricted based on income and property qualifications, effectively disenfranchising native Hawaiians.

This new political structure laid the groundwork for increasing American dominance. While the Hawaiian people still retained a deep cultural identity and connection to their monarchy, their political autonomy was slipping away. The Bayonet Constitution was a key step in the erosion of Hawaiian sovereignty.

Queen Liliʻuokalani and the Overthrow

Queen LiliÊ»uokalani ascended to the throne in 1891 following the death of her brother, King KalÄkaua. A strong advocate for Hawaiian sovereignty, she sought to restore the monarchy’s authority and draft a new constitution to replace the Bayonet Constitution. Her actions alarmed the American and European elite, who feared a loss of power and economic privilege.

In 1893, a group of American and European residents, with support from the U.S. Minister to Hawaii and a contingent of U.S. Marines from the USS Boston, orchestrated a coup that overthrew the Queen. She was arrested and imprisoned in her own palace. The insurgents established a provisional government led by Sanford B. Dole, a key figure in the annexation movement.

U.S. Reaction and Delay in Annexation

Initially, President Grover Cleveland opposed the coup and demanded that Queen Liliʻuokalani be restored to power. He sent a representative to investigate and concluded that the overthrow had been illegal. However, the provisional government refused to relinquish control, and Cleveland was unwilling to use force to reverse the situation.

For a time, the idea of annexation was put on hold. Yet the situation changed with the election of President William McKinley in 1896. A strong advocate of expansionism and a believer in the strategic value of the Hawaiian Islands, McKinley supported annexation efforts more openly.

The Spanish-American War and Strategic Importance

The Spanish-American War in 1898 served as a turning point in the annexation process. The United States realized the importance of having a mid-Pacific naval base to support its military operations in the Philippines and other territories. Pearl Harbor, already an important port, became essential to U.S. interests.

National security arguments combined with the economic influence of American planters and the strategic advantages of the islands ultimately led Congress to act. The annexation of Hawaii was seen not only as a territorial gain but also as a military necessity for the growing American empire.

Annexation and the Organic Act

On July 7, 1898, the Newlands Resolution was passed by Congress, formally annexing Hawaii as a U.S. territory. Unlike other territorial acquisitions that involved treaties, Hawaii was annexed by joint resolution, bypassing the need for international agreement. This action ignored the will of native Hawaiians, the former queen, and much of the local population who opposed annexation.

In 1900, the Organic Act established the Territory of Hawaii and granted U.S. citizenship to its residents. While some welcomed American governance, others viewed it as the continuation of colonialism. Native Hawaiians became a minority in their own land, facing economic challenges, cultural suppression, and political marginalization.

Native Hawaiian Resistance and Legacy

Resistance to annexation persisted long after 1898. Native Hawaiian leaders submitted petitions, organized protests, and advocated for self-determination. The most famous expression of opposition came in the form of the KÅ«Ê»Ä Petitions, signed by over 21,000 Hawaiians, demonstrating broad resistance to the annexation effort.

Despite these efforts, Hawaii remained a U.S. territory until it was granted statehood in 1959. However, the annexation left deep scars. Hawaiian language, culture, and traditional practices were suppressed for decades. Generations of Hawaiians have fought to preserve their identity and seek justice for the loss of their sovereignty.

Modern Reflections and Apology

In 1993, on the centennial of the overthrow, the United States Congress passed the Apology Resolution, formally apologizing for the role the U.S. played in the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The resolution acknowledged that the native Hawaiian people never relinquished their sovereignty through a vote or agreement.

This gesture, while symbolic, was a major step in acknowledging the injustice of annexation. It also helped inspire a resurgence in Hawaiian cultural pride, language revitalization, and political activism aimed at securing greater recognition and rights for indigenous Hawaiians.

The American annexation of Hawaii was not a straightforward or peaceful process. It involved political manipulation, economic interests, and military intervention. Native Hawaiians were largely excluded from decisions about their own land and future. Over time, the annexation helped transform the United States into a Pacific power, but it also represented a profound loss for an independent nation with its own rich culture and history.

Today, the legacy of annexation continues to shape Hawaiian society. Questions about sovereignty, land rights, and cultural identity remain central to many Hawaiians. The story of annexation is a reminder of the complex interplay between empire and resistance, and the enduring impact of colonial actions on indigenous peoples.