The pituitary gland, often referred to as the ‘master gland’ of the body, plays a vital role in regulating various endocrine functions. Its development during embryology is a complex and fascinating process that involves multiple embryonic tissues and precise timing. Understanding the embryology of the pituitary gland is essential for grasping how this small but powerful gland orchestrates hormone production throughout the human body. This topic provides a clear and detailed overview of how the pituitary gland forms, emphasizing its dual origin and the stages involved in its differentiation.

Embryonic Origins of the Pituitary Gland

Dual Developmental Origin

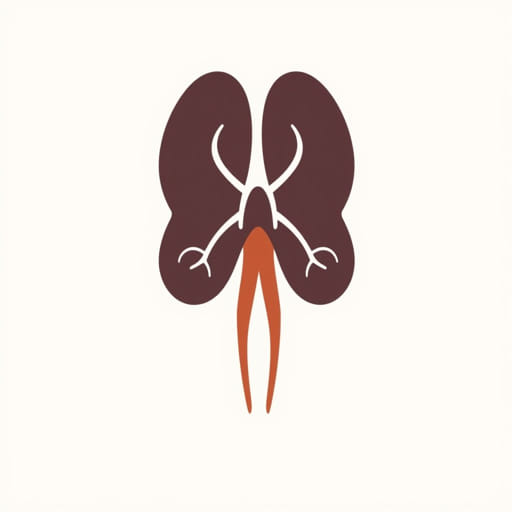

The pituitary gland develops from two distinct embryonic tissues: ectoderm from the oral cavity (Rathke’s pouch) and neuroectoderm from the floor of the diencephalon. These two components eventually merge to form a single functional gland composed of an anterior and a posterior part, each with different origins and functions.

- Anterior pituitary (adenohypophysis) originates from oral ectoderm

- Posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis) arises from neuroectoderm

This dual origin is critical to understanding how the gland functions, as the anterior and posterior portions are structurally and functionally distinct.

Development of Rathke’s Pouch

Formation from Oral Ectoderm

The development of the anterior pituitary begins around the third week of gestation. A small pocket of ectodermal cells invaginates from the roof of the primitive mouth (stomodeum) to form Rathke’s pouch. This structure is non-neural in origin and represents the start of the adenohypophysis.

As Rathke’s pouch grows upward, it moves toward the developing brain. By the fifth week, the pouch detaches from the oral cavity and comes into contact with the infundibulum, an extension of the diencephalon. This contact is crucial for further differentiation and development.

Formation of the Neurohypophysis

Development from Neural Tissue

While Rathke’s pouch is forming, a downward extension from the diencephalon begins to grow toward it. This neural structure, known as the infundibulum, eventually becomes the posterior pituitary or neurohypophysis.

The infundibulum gives rise to the pituitary stalk and the pars nervosa. Unlike the adenohypophysis, which produces hormones, the neurohypophysis stores and releases hormones synthesized in the hypothalamus, such as oxytocin and vasopressin (ADH).

Fusion of Anterior and Posterior Parts

Integration into a Single Gland

By the end of the sixth week, the two components Rathke’s pouch and the infundibulum begin to integrate. The cells of Rathke’s pouch proliferate and differentiate into several distinct regions of the anterior pituitary, including:

- Pars distalis the largest region, responsible for most hormone production

- Pars intermedia a thin layer between anterior and posterior lobes

- Pars tuberalis wraps around the infundibulum

Meanwhile, the infundibulum continues to develop into the pars nervosa of the posterior pituitary. Axons from hypothalamic neurons extend into this region, forming a neurovascular interface that enables hormone release into circulation.

Cell Differentiation in the Adenohypophysis

Specialized Hormone-Producing Cells

As the anterior pituitary matures, it becomes populated by specialized cells that secrete different hormones. These include:

- Somatotrophs produce growth hormone (GH)

- Lactotrophs secrete prolactin (PRL)

- Corticotrophs synthesize adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

- Thyrotrophs produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Gonadotrophs release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

These cells differentiate in response to signaling molecules and transcription factors, such as Pit-1, Tbx19, and Prop-1, which guide the development of specific cell lineages within the gland.

Hormone Regulation and Pituitary Function

Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis

By the end of the first trimester, the pituitary gland is functionally integrated with the hypothalamus. This connection is essential for the regulation of hormone production via the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. The hypothalamus secretes releasing or inhibiting hormones that travel through the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary, modulating the release of hormones like GH, TSH, and ACTH.

The posterior pituitary, though not producing hormones itself, serves as a storage site for neurohormones synthesized in the hypothalamus. These hormones are transported down axons and released into the bloodstream when needed.

Clinical Relevance of Pituitary Embryology

Congenital Pituitary Disorders

Understanding the embryology of the pituitary gland is essential for diagnosing and managing congenital disorders that arise from developmental defects. Some conditions linked to abnormal pituitary development include:

- Hypopituitarism reduced hormone production due to underdevelopment

- Craniopharyngioma a tumor arising from remnants of Rathke’s pouch

- Septo-optic dysplasia a syndrome involving midline brain defects and pituitary dysfunction

Many of these conditions can affect growth, metabolism, and reproductive function. Imaging and genetic testing are often used to confirm diagnoses rooted in embryological abnormalities.

Evolutionary and Comparative Insights

Conserved Development Across Species

The development of the pituitary gland follows a remarkably conserved pattern across vertebrate species. In many animals, the gland also arises from the fusion of oral ectoderm and neural tissue, reinforcing its evolutionary importance as a central endocrine regulator.

Studies in model organisms such as zebrafish, mice, and frogs have provided invaluable insights into the molecular pathways guiding pituitary formation, which in turn help inform human developmental biology.

The embryology of the pituitary gland is a prime example of how complex tissue interactions give rise to a critical organ system. From the invagination of Rathke’s pouch to the integration with the diencephalon’s infundibulum, the gland’s development reflects precision and coordination. Understanding the origin and differentiation of the pituitary gland not only enhances our knowledge of human development but also provides essential context for various endocrine disorders. As research continues to uncover the molecular underpinnings of pituitary formation, medical science will be better equipped to treat and prevent related conditions effectively.