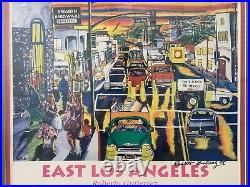

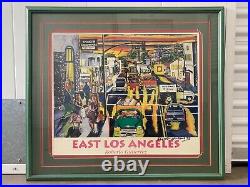

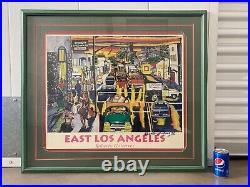

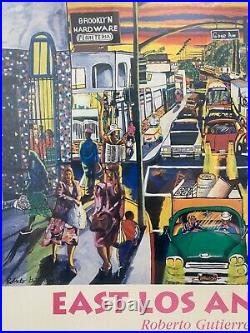

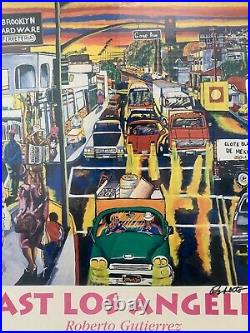

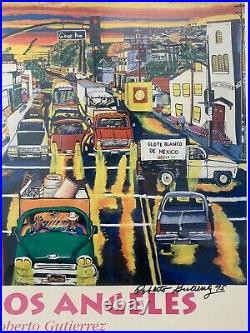

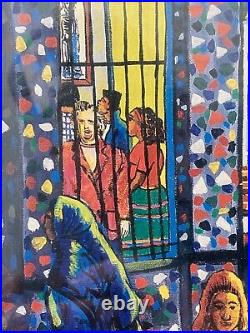

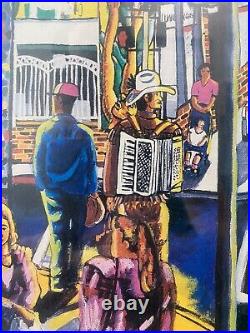

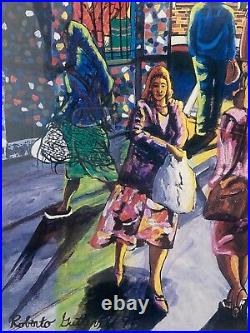

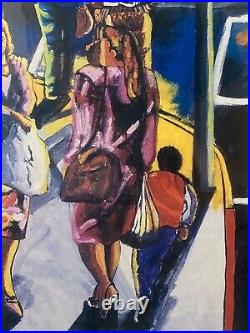

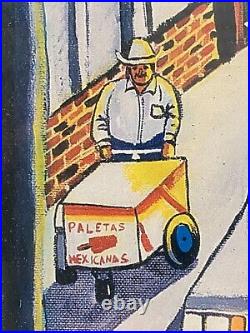

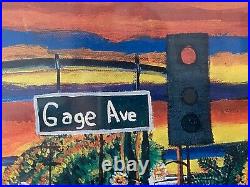

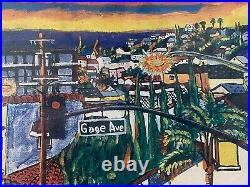

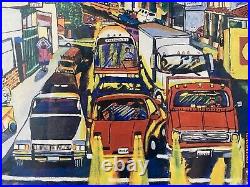

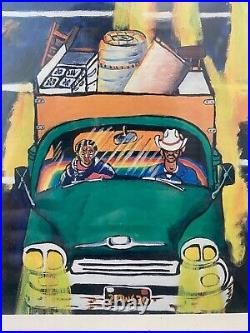

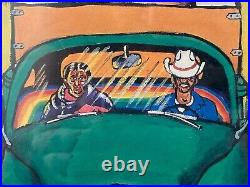

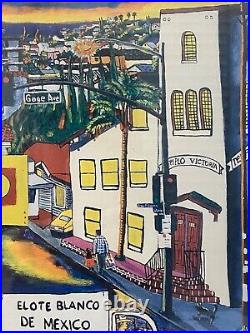

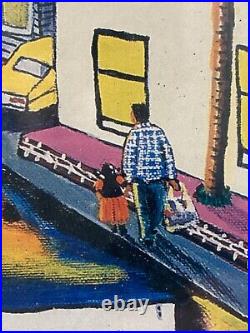

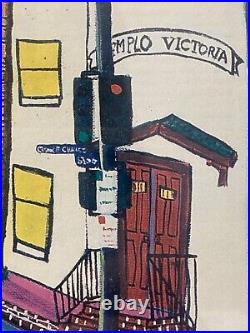

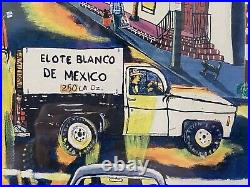

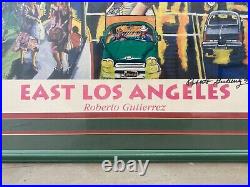

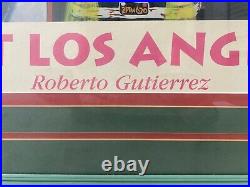

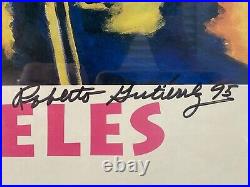

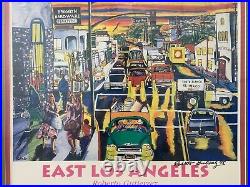

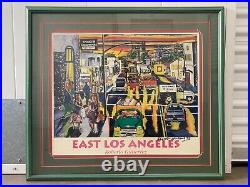

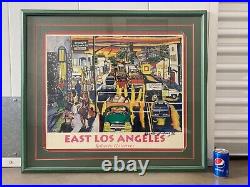

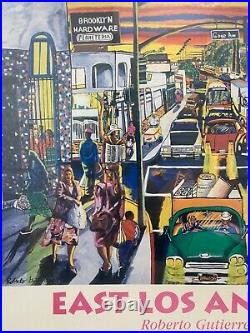

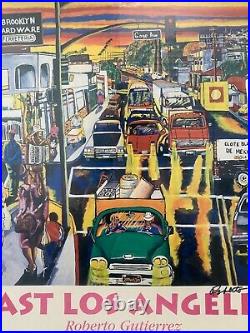

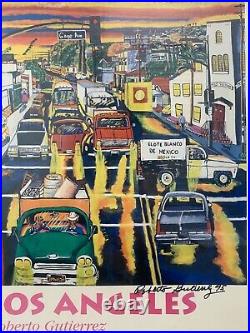

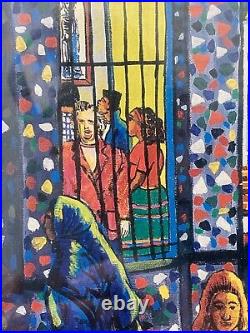

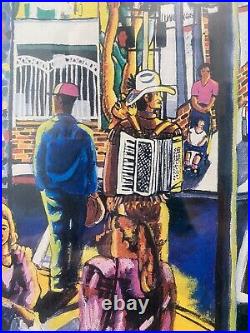

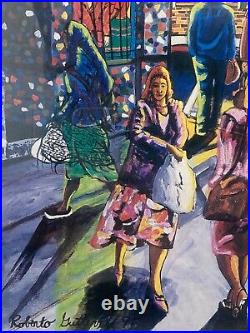

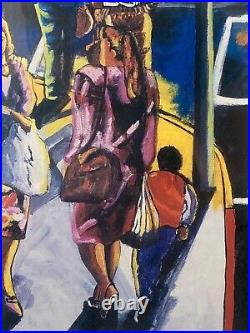

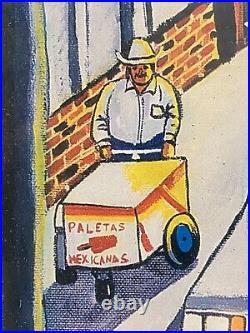

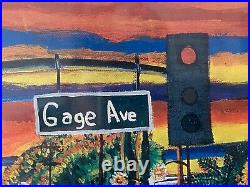

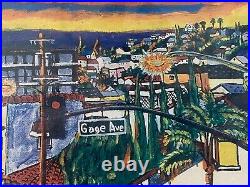

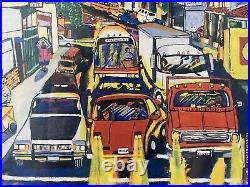

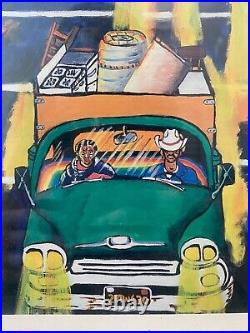

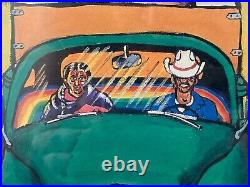

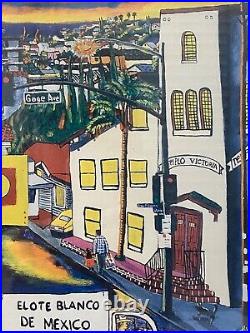

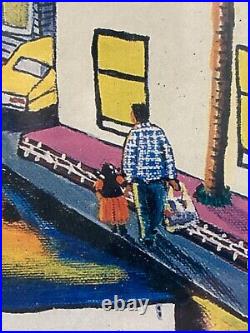

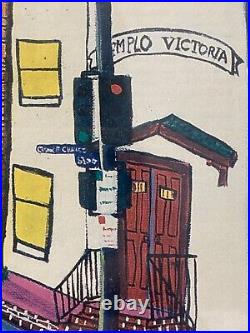

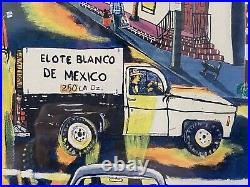

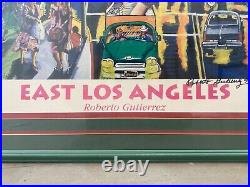

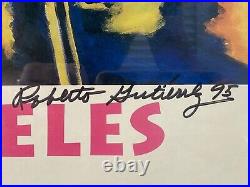

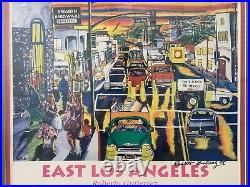

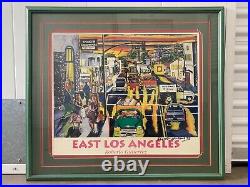

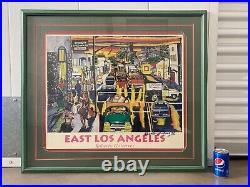

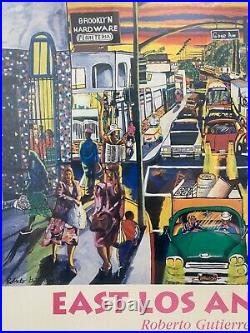

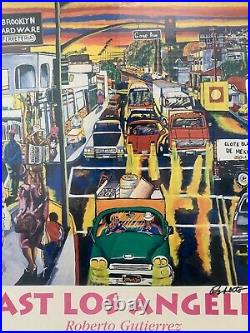

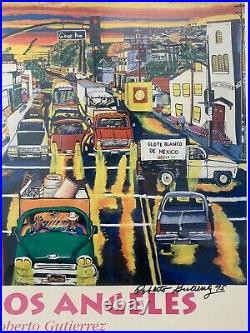

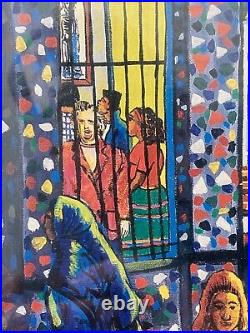

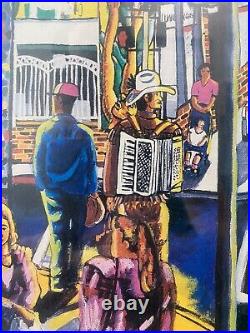

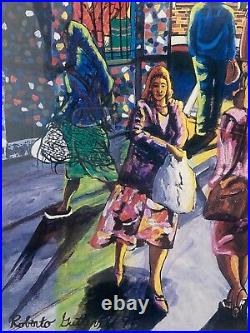

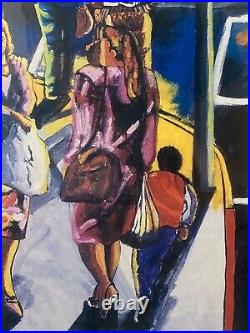

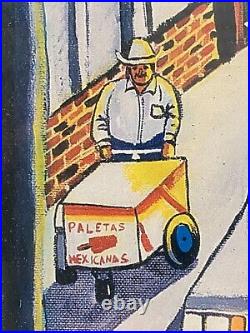

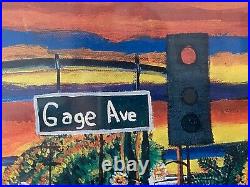

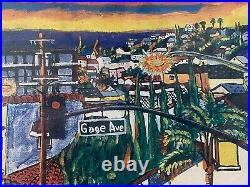

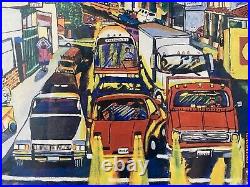

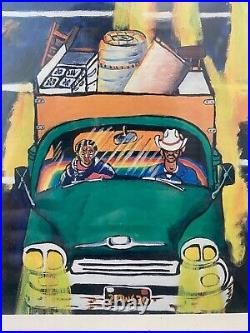

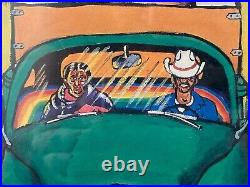

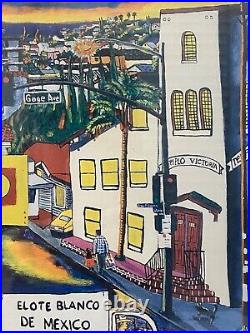

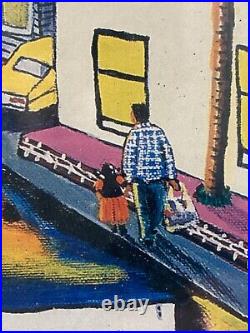

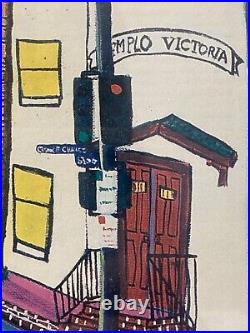

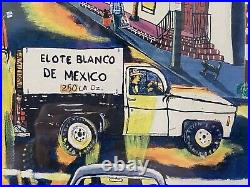

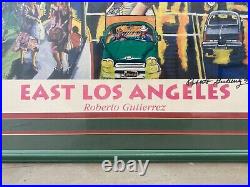

This is a culturally important and Very RARE Vintage Chicano Mexican Art Exhibition Poster, titled East Los Angeles, by esteemed Southern California Chicano artist Roberto Gutierrez b. This artwork depicts a bustling cityscape scene in East Los Angeles, with signs for Gage Ave. And Cesar Chavez Blvd. Visible in the distance. This artwork depicts a rain slicked road at sunset, with numerous vehicles passing through the center of the scene. Off to the sides, a paletero man, a small church service, and Latino families can be seen walking along the sidewalks. Hand signed and dated by the artist at the lower right edge: Roberto Gutierrez 95. Approximately 27 1/2 x 31 1/2 inches including frame. Actual visible artwork is approximately 19 1/4 x 27 1/4 inches. Good condition for age, with some light scuffing and paint loss to the original period frame please see photos. This particular variant of Gutierrez’ poster has never been offered for sale before, and when these pieces do come on the market, they are never hand signed by the artist. Original artworks by Roberto Gutierrez are prominently displayed in the permanent collections of the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture of the Riverside Art Museum and held in many public and private art collections worldwide. Acquired in Los Angeles County, California. If you like what you see, I encourage you to make an Offer. Please check out my other listings for more wonderful and unique artworks! Chicano artist Roberto Gutiérrez is one of the most important artists to come out of the East Los Angeles artistic boom of the early 1970s. However, he has been largely ignored. This essay explores Gutiérrez’s life and the significance of his work to the evolving Chicana/o artistic narrative about Latino life and aesthetics in Los Angeles. In particular, it explores the way in which Gutiérrez’s oeuvre reflects and creates an image of urban Los Angeles that is distinctly Latino and working-class. The Avenue Studio proudly presents Roberto Gutierrez – Paintings. Roberto Gutierrez, painting for over 30 years, is one of the more important artists to come out of East Los Angeles. His inspiration comes from the gritty streets where daily he walks, and the coffee houses and bookstores he frequents. Roberto sketches incessantly all he observes which later becomes an acrylic or gouache painting. This current body of work exhibited represents a small but significant cross-section of Gutierrez’s historical record, including his Paris series. His work has been widely shown in galleries throughout the Southwest. Many of his paintings have been the possession of former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. Roberto Gutiérrez: Vietnam Veteran, Chicano Artist Capturing the Colors of Life. His life’s journey — walking through the bloodied soils of Vietnam, through the halls of East Los Angeles College, up and down the marbled floors of the finest museums in Europe, and retracing the steps of his artistic heroes in Montmartre, France – all have influenced him to become the renown painter he is today: incapsulating landmarks, streets. Everyday people, capturing imagery of colors and shapes that transition from realism to impressionism to abstract. Roberto Gutiérrez left Los Angeles in 1961 as a naïve 17-year old figuring the U. Marines was a great way to escape his difficult childhood. And, he guessed, it was a way to get an education and improve his future potential – at what? Well, here he was clueless. Robert “Bob” Gutiérrez, U. Marine Corps, having served and survived the horrors of Vietnam without ever discovering what he would do for the rest of his life. Thankfully, Gutiérrez did eventually find his life calling. Today, Chicano Studies scholars rate him as one of the most important Chicano artists to come out of the Los Angeles 1970s’ boom. Gutiérrez, now 73, is the first to admit that he is an emotional painter. It could be a traumatic childhood or Vietnam memory that might dictate if he uses thick black paint with wide abstract strokes, like the ones he used for his recent 6th Street Bridge collection. The bold black represents the great sadness that this iconic L. Landmark that connected the east to west has a date with a wrecking ball. “This bridge was a big deal back when Los Angeles was a younger city, ” recalled Gutiérrez. He walked across it dozens of times from childhood to the present. Witnessing the bridge as a newbie to now seeing it’s demise, breaks my heart. This collection represents the metaphor for life. You’re born, you go through life and then you die. That’s how this collection’s images came to life. There are also paintings that represent more playful emotions, street scenes filled with color and images of his gente (people), living mundane days with unshakable faith and hope-images associated with a Latino community. Gutiérrez’s work has evolved from looking more like photographs to instead challenging his imagination by capturing the strong feelings rather than the literal image. And then there is his breathtaking 2013 Paris collection. Images seize the positive of our neighborhoods and landscapes, his Paris collection morphs the spirits of painters: figurative impressionist Édouard Manet, post-impressionist Vincent van Gogh, landscape impressionist Claude Monet and expressionist Chaim Soutine. “Paris does something to me, ” Gutiérrez said. When I see a particular sight in Paris, I just run with it. I run with my feelings. One painting may look like an impressionist painting and another one may impress me differently and remind me of Soutine, whose paintings depending on his mood may look a little like he might have been on acid when he painted it. I just go with it. Paris brought out the best of my figurative impressionist paintings. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve evolved more into abstract images. “I believe my new European collection will be more abstract, but we’ll see what comes out of me, ” Gutiérrez said. I may start it one way but the ultimate result is unknown to me until I’m done. That’s what painting with your emotions does to you. I’m very excited to be returning to Paris. Eating at one of his favorite Italian restaurants recently, he was asked if he had retired. “There is no such thing as retirement for poor people, ” he chuckled with the same youthful sparkle in his eyes. Gutiérrez continues to paint and teach a mixed-media art class at Plaza de La Raza in Lincoln Heights. Gutiérrez is currently also part of the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) new exhibition “Somewhere Over El Arco Iris: Chicano Landscapes, 1971 to 2015, ” which runs through Nov. MOLAA is open Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday from 11 a. M to 5 p. Friday from 11 a. Admission is free only on Sunday. This Veterans Day, Lance Cpl. Robert “Bob” Gutiérrez will pay tribute to several memorial ceremonies throughout the city of Los Angeles. But he will never, ever discuss his Vietnam experience – these emotions are revealed only in his paintings. Yet you know it is important because the few hanging photos in his home are of his buddies, many whom never made it back. Roberto Gutiérrez: The Alchemy of Magical Brushstrokes and Metropolitan Landscapes. Artist and studio painter Roberto Gutiérrez isn’t pulling any punches these days. In fact, it wouldn’t be an overstatement to say the native son of L. S Eastside is coming up aces more often than not. And when he isn’t walking away from his latest self-imposed challenge with a resounding victory, he’s holding his own with a combination of skill, panache and charisma that forces a split decision in his favor. And with the title belt all but his, he’s primed and ready to face off once more with a few of the most important metropolitan centers in the world. Increasingly revered as master of the urban landscape-rich and distinctly enunciated personal panoramas from “el mundo Gutierrezano”(the Gutierrezian world)-he remains an artist beyond the pale. A recent solo exhibition at the edge of a small, unlikely lake in the Los Angeles Lincoln Heights district is the most emphatic affirmation yet of a simple, unspoken truth: Roberto Gutiérrez is the most important Chicano artist you’ve never heard of. And that isn’t his problem. It isn’t my problem. Roberto Gutiérrez: The Evolution of a Contemporary Artist-Magical Brushstrokes of Metropolitan Landscapes. The spry, paintbrush and graphite-wielding septuagenarian waltzes out of the hometown corner with welterweight grace. Reared in the somewhat hard-knock but still irrepressibly noble barrios of Los Angeles, he offers up, as an unblemished score card, the record of his date with the foremost metropolis in the nation. The unanimously riveting visual diary-worthy of a Madison Square Garden spectacle-brims with the streets, the pedestrian pathways, the built environments and the natural landscapes of Manhattan. Deftly curated by Gabriel Jiménez at the Plaza de la Raza Boathouse Gallery in Lincoln Park, the selection of paintings and works on paper-inspired by the Eastside enclaves he came of age in, his twin pilgrimages to Paris, L. S late Sixth Street Bridge, and, ultimately, even Gotham itself-bristle with big-city light and luster. They also echo and twist with the indelible love and loss that make borders, city limits and nation-state boundaries meaningless. Rendered by the artist in acrylic on canvas, graphite on paper or with various ink, gouache, and tie-dye combinations, the factories, museums and office towers we recognize from a familiar Manhattan skyline hum and resonate as much with the humanity of the crowds passing through them daily as they do with historical or architectural significance. Executed over the last three years, the results of his affair with Hong Kong on the Hudson are a fitting finale to the three-part survey of a career that merits serious study and examination. (Gouache, Sumi Ink and Tie-dye) and. Central Park in the Winter. (Acrylic on Canvas) are no more or no less sacred than the. (Sumi Ink and Tie-dye) or a. Water Tower in Manhattan. (Sumi Ink and Tie-dye). From the serenity of a snow-riddled Central Park scene to the obscure beauty of. Little Brazil & 46th Street. What becomes most clear in the crowning segment of this highly anticipated evolutionary assessment-is that Gutiérrez, the artist, is at home anywhere. “Of course I was always Chicano, but before any of that, I was just another one of those [Mexican] street urchins, ” Gutiérrez says. As a kid, I used to walk downtown to shine shoes, and I thought I’d hit the big time when I could charge ten cents instead of a nickel. If hunger and hardship at home shaped his childhood during the 1940s and’50s in Chinatown, Boyle Heights and East L. Combat in Vietnam as a U. Marine reinforced the futility of dreams and aspirations. Enlisting at 17, he was guaranteed “three squares a day” and found purpose in the regimen of military routine. That illusion evaporated, he confesses, during a mental breakdown leading to his discharge. “When I got out of the military, I took a drawing class at East LA College, and realized I couldn’t draw, ” he says. Turning to abstract art, he nonetheless favored, he recounts, the “Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and Fauvists” until he was confronted, berated and cajoled by legendary Self Help Graphics founder Sister Karen Boccalero. “She insisted I make figurative work, ” Gutiérrez recalls. And she encouraged me to come home in my art. Was scheduled to close in January but extended to accommodate more gallery traffic than usual. According to Brenda Herrera, principal at a PR firm representing him, Gutiérrez taught art at Plaza de la Raza for over 20-years. “He retired two years ago, but everybody remembers him, ” Herrera says. With curatorial authenticity derived from a familiarity with and the inclusion of several important early works, the exhibition is pays heed to the artist’s deliberate use, during that formative period, of heavy lines and a slightly skewed perspective. The dark outlining of both human figures and inanimate subjects imbues them with a playful defiance. (Acrylic on Canvas), centered on a Little Tokyo landmark, the storefronts, asphalt and pavement are living, breathing repositories of a community’s history and heart. Their innate cultural validity-agency, alluded to in the saturated color, opposes erasure or relegation to phantom invisibility. Paintings such as C. Ity Terrace, Eagle Street and City Terrace Drive. Provide a similar refrain, albeit in less commercial, primarily residential corridors of historic East L. These earlier works, foreshadow the more painterly concerns evident in the second suite of works installed in the middle section of the gallery. Gestated during a pair of trips to the French capital, two pieces here. (Acrylic on Canvas) and. Last Light Ile de la Cite. (Black & White) evoke a style I’ve described elsewhere as architectural abstractionism. ” Both depict austere and haunting spaces in working-class Parisian “arrondissements. There, Gutiérrez retraced the Montemarte meanderings of Van Gogh, Cezanne and Gaugin, artists who broke from Impressionism and rejected schools of impersonal realism or representational. In this context, it is worth noting that a number of the Paris-inspired works feature old-world architectural elements-windows, street lamps and staircases-that verge on form-based abstraction but nonetheless invoke emotional depth and vulnerability. Wild Ride on 6th Street Bridge. (Acrylic on Canvas) delivers an intensely visceral flood of foreboding, despite a limited palette. While ostensibly figurative, the painting seems intentionally fraught with a dangerously irreverent eagerness to dance lasciviously with a less than latent abstract expressionism. The subject of the painting, a car careening out of control atop the bridge, is symbolic. One false note, a single misstep, an unintended line or an accidental brushstroke from the hand responsible for. Is all that this recalcitrant abstraction needs to send the car over the edge, usurp the narrative and subvert the otherwise civilized Gutiérrez send off in honor the iconic bridge he was sorry to see destroyed. By contrast, series of smaller gray-scale paintings depicting concrete and steel bridge details from the demolished steel girder structure-intentionally hung in an abstract pyramid pattern-is collectively rife with a forlorn sadness that coexists with each painting’s geometrically abstract, detached reference to the lost viaduct. Culled from a specific series called. Elegy to the 6th Street Bridge. Which debuted at Ave. 50 Studios, Gutiérrez says, they were the result out of a dark pall that descended upon him after a return from the second excursion to Paris and the successful opening of a likewise gray-tinted collection inspired by the 1930s and’40s noir legacy in Los Angeles. I felt like it was time to come home. I was ready, Gutiérrez says, referring to the genesis of the aforementioned exhibition of work based on L. That was really how the. The wrecking ball that not long ago annihilated the bridge which had loomed so heavily over his past and in his imagination was simply a reminder that even monumental cement and steel wonders, like celluloid archives, are ephemeral vanities at best. For Gutiérrez, who has courageously painted his way through murkier and bloodier terrain before, there remained one more distant prize on the horizon, one that harkened back to his boyhood walks along Broadway at the height of an era when movie palaces-the Million Dollar Theater and The Orpheum, for example-glittered nightly with neon. First run films, red carpet premieres and Hollywood stars were frequent fixtures in and around L. S original Broadway Theater District then. Because it was Broadway, you automatically thought of New York. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, says Gutiérrez. He credits Gabriel Jiménez and Plaza de la Raza Executive Director María Jiménez for their belief in the viability of an exhibition based on the evolution of his work over time. His late bloomer travel opportunities, he exclaims, have all been dreams come true. “Everyone was getting ready for Christmas, ” he says about his inevitable beeline to the oft-cited center of the art world. We rode around Central Park in a horse-drawn carriage. So, yes, I feel very lucky, says Gutiérrez. His genuine excitement and joy are effusive. They are occasioned by the tangible reflection of his aesthetic trajectory over the last several decades gathered in a formidable retrospective. Grouped together as one “suite” in a semi-enclosed space to the immediate left of the gallery entrance, the East L. Landscapes and a few of the bridge works function as the first of three segments or chapters. The roughly 20 combined works, however, would have made an equally beautiful stand-alone exhibition. The Paris-inspired paintings and drawings and several more. Pieces fill the central section of the exhibition space, which includes a wall that creates a small entrance foyer just inside the double-door entryway. On the wall facing the entrance hangs. It is nothing short of magnetic and literally radiates as the single piece of art that gives. A tender and timeless cohesion. In a strangely mystical way, the painting has been transformed, as if by some other-worldly alchemy. Ceases to be merely a romantic dream destination for an artist who is the embodiment of anomaly. Through the power of multidimensional transmutation, the painting becomes the bridge Gutiérrez grieved for when he learned of its demise, the doorway that carried him over the L. River from Boyle Heights to the center of the City of Angels, once upon a time. No longer content to span what is now just a cement-lined flood-control channel, the painting-as-park-cum-bridge has remolded and reshaped itself beyond the limits of causality and quantum physics. Guided by visionary arch-alchemist Roberto Gutiérrez, it now stretches from L. S Eastside to Midtown Manhattan, then leaps directly to Paris where it will stand guard over the River Seine at sunset, from here to eternity. Art of Marine veteran who paints as therapy on exhibit in Lincoln Heights. LOS ANGELES (KABC). Artist Roberto Gutierrez says color is in his DNA. He expresses that in his paintings, after having lived through the darkness of war. It’s my soother for PTSD. Still going through that, said Gutierrez. Never will get rid of it but it’s better. For more than 40 years, Gutierrez has been painting away the pain of the Vietnam War. Marine veteran is among just a few members of his platoon who made it home alive. Today, Gutierrez is a distinguished artist known for painting Los Angeles landscapes. His current exhibit at Plaza de la Raza also celebrates landscapes from New York and Paris. I got the bug for Paris when I started to be a young art student at East L. Junior College and I wanted to see those places Monet was at, and Manet, and then Picasso and Degas and all these guys. College is where he discovered art, and he’s been painting ever since. It is, in some ways, medicine for his post-traumatic stress disorder. “I continue to seek help, ” said Gutierrez. I’ve tried the kitchen sink. I’ve tried hypnosis. I’ve tried traditional therapy. I’ve tried Qigong. I’ve tried Tai Chi. Gabriel Jimenez, the curator at Plaza de la Raza, is especially fond of what this artist represents. “Resilience, person of color, instructor, teacher, mentor, history buff, ” said Jimenez. Chicano from this area showcasing the beauty of Los Angeles. This colorful exhibition runs through Feb. 16 at Plaza de la Raza in Lincoln Heights. The Cheech: A Tribute to Chicano Culture. This past summer, I had the privilege to visit The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture; an experience that inspired an exploration of my identity and heritage. Despite my Chicana roots and love of the arts, I had never heard of this museum. My tia and prima were the ones that suggested going. Up until that point, I had only heard of studios or exhibitions dedicated to Chicano art, but never an entire museum. I immediately felt a sense of pride for the step forward in the battle for Chicano visibility and representation. On my ride to the museum, I was delved deep into my brain, searching for an answer to where I had heard “Cheech” before. I remembered the iconic duo Cheech and Chong and was stunned to learn that Cheech Marin was not only an actor and comedian, but an activist and major supporter of Chicano Arts. It turns out that he. Owns one of the most extensive collections of Chicano art in the world. Containing over 700 pieces of artwork. In fact, the Cheech was born from this very collection. From February 2 to May 7 of 2017, the Riverside Art Museum (RAM) held the exhibit. Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper. Containing a few of his collected works. It showcased 65 pieces from 24 Chicano artists. Admissions for the exhibit soared, nearly attracting 1,500 attendees, and greatly exceeding the normal amounts of admission revenue. The success of this exhibit exemplified the demand for Chicano art and opened the floor for a partnership between RAM, Riverside, and Cheech Marin. Cheech donated his collection to RAM. And just a couple years later, on. June 18th of 2022. The Cheech opened its doors to the public, occupying a small building just across from the renowned Mission Inn in Riverside’s historic district. This resulted in the beginning of its legacy as a pillar of and devotee to Chicano Arts. Together, we hope to bring every aspect of Chicano art to this region as well as the rest of the world. We have something wonderful to give. Immediately after entering the Cheech, I was amazed by the massive amounts of culture within. I flocked to all walls and corners of the building, taking my time with each piece of artwork in order to appreciate the beauty, community, and connection I felt with each. In my time covering all. I saw Chicano history in Vincent Valdez’ oil painting Kill the Pachuco Bastard! ” I witnessed past struggles and sorrows in Judithe Hernández’ “Juárez Quinceañera. I resonated with Alaniz Healy’s “Una tarde en Meoqui”, which painted the picture of a family, smiling and serving each other food. Whispers of representation and connection filled the quiet, pensive halls of the galleries. These were reinforced by remarks like That looks like your Tio Martin! While staring at works by César A. Martínez, and “Parece a la casa de tu abuela, ” referring to a painting by Jacinto Guevara. I, too, saw my family in the painted faces and locations. One of the first paintings we looked at was “City Terrace” by Roberto Gutiérrez. My tia pointed, Your Abuelito Jose used to live near there. My heart fluttered. I never had the chance to meet my abuelito, for he had passed before I was born. Somehow this painting gave him life, bringing me just a little closer to him, his experiences, and the history of my family. Representation matters, and The Cheech provides it for many Chicanos. It is an answer to the questions Who are the people of Los Angeles? What is their story? An answer that has long been ignored and hidden, many times forcefully so. The history and voices of the Chicano community have largely been pushed away from the American narrative, despite all the contributions that we have made. Chicano successes have been minimized and omitted from textbooks and other media for decades. This white-washed version of history has and continues to create generations of Mexican-Americans that have no knowledge of our people’s past victories and defeats, and no role-models, resulting in a lack of motivation to embrace our origins and culture. The Cheech is an important step to halting this erasure by weaving the story of Mexican-American people back into the public’s attention, creating a more complete look at the history of the United States, the very goal of Chicano art. According to the museum, Chicano art is the art of struggle, protest, and identity. ” The genre can trace its origins back to the Chicano Movement or “El Movimiento, in which artists used their work as a means of political and social advocacy. Chicano art then evolved to simply be a representation of their community, not necessarily focusing on any political aspects but instead reflecting on the story of the Mexican-American experience. It can be highly personal. But what I’ve learned over the years is that Chicano art reveals the sabor (flavor) of the community. The evolution of Chicano Art was exemplified perfectly through. The Cheech’s first temporary show, Collidoscope: de la Torre Brothers Retro-Perspective, which featured mixed-medium works, including lenticulars, glassblowing, and technological elements, by brothers Einar and Jamex de la Torre. Their centerpiece is a. 26 foot tall lenticular of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue. Who shifts into new form, incorporating various symbols of Chicano identity, as the viewing angle changes. On the second floor of the museum, the show. Included around 30 years of work. From the De La Torre Brothers. Born in Guadalajara and raised in the United States, integrated themes of pre-Columbian art, Catholic symbolism, and Mexican culture throughout their pieces, each reflecting the Latino experience within the American way of life. Each piece of artwork had so much to say and so much to offer beyond their gleaming aesthetics and beauty. One piece that stood out to me from this show was a mixed-media portrait titled “Soy Beaner”, which diplayed a range of Chicano as well as Eastern religious symbols, all within the structure of an Aztec Calendar. The symbols included flying Guadalupes, dragons, lizards, crabs, Mexican beer bottles, and much more. The description of the piece stated that it was meant to illustrate the fluidity of culture and identity. The title is not only a play on words, but it represents the reclaiming of a derogatory term as well as a jab at the fact that some traditional Mexican crafts are now mass produced in China and then consumed back in Mexico. Attending this museum, I felt submerged in a culture and identity that I have yet to fully explore. Unfortunately, I learned so much more about the history and experiences of Chicanos than I ever did in a classroom on this visit to The Cheech. This sad reality speaks to how fundamental The Cheech is to helping build a Chicano identity and repairing the damages done by those who have tried to bury it under white-washed records of the past. The success of The Cheech has shown us that the Mexican-American community is on its way to reclaiming our heritage and distinguishing ourselves as a people who have persevered through decades of discrimination. It is the gentle signifier that, despite derogatory remarks, accusations of being “murderers and rapists, ” and battles against direct and hostile racism, whether it be during the infamous Zoot Suit riots or current day, we matter. We have offered much to this country and will continue to do so. It is an exclamation against erasure, proving that history cannot cast us aside. The Cheech is an homage to the contributions of Chicano people, our losses, our wars, and our triumphs. It is an inspiring and thought-provoking experience, which I highly recommend to everyone, Chicano or not. Thank you Cheech Marin for this incredible sanctuary for dialogue surrounding the Chicano identity and the Mexican-American narrative. The Gritty Landscapes of Roberto Gutierrez. His paintings in this context are classic L. Noir, straight out of James Ellroy’s L. Confidential, and often rendered from photographs that are sometimes blurry and spotty, which is also incorporated into the painting to give it a more authentic feel. Roberto Gutierrez was born in 1943 in Los Angeles to a family at the edge of poverty and the youngest of nine children. They moved around a lot from Lincoln Heights, to Chinatown, to Highland Park, and then to Boyle Heights where he attended school at Roosevelt High. After graduating, with no job prospects and with inadequate internal turmoil for being an economic burden to his family, he volunteered to the U. Marine Corps and joined the Vietnam War. His time spent in boot camp was rewarding because at home he never had three meals a day, a bed with two sheets, a clean pillow and warm blanket, petty cash, but most importantly — his confidence multiplied. His mother and siblings weren’t of the warm idyllic stock that is often referenced in popular Latino culture, on the contrary, they were cruel and heartless and often tormented him, thus crushing his self-worth. It seemed he had found the answer in a strict military environment. And unlike many of his counterparts who went on to college and launched the intellectual framework of the Chicano Movement, Roberto was drawn to the conservative agenda learned in the service. But after six years of engaging in military conflict with the death toll increasing and closing in on him, he had a nervous breakdown after his father passed away back home and Roberto ended up at a naval hospital in San Francisco, and six months later, he was back in L. Where he would forever physically abandon the ravages of the battlefield. This period marked the return of the prodigal son, the spiritual return to his father even though he was physically removed. It was then that a new grasp on reality was needed. After several months of working a dead-end job and living without purpose, he used his G. Bill and enrolled in East Los Angeles Community College and was introduced to artists such as: Chaim Soutine, Monet, Van Gogh, Manet, Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, films like. The Battle of Algiers. The Souls of Black Folks, Nobody Knows My Name, Native Son. And the political culture of protest that surrounded him. Around this time he took up painting and began with the trauma experienced in Vietnam and the angst of his childhood as if reconciling the wrongs he had observed or were imposed on him. Mostly inspired by Soutine, Roberto Gutierrez went through a period where he experimented with painting rotting dead fish and chickens, and even a pig’s head, and although cathartic and necessary, it didn’t win him an audience. He had also started painting a self-portrait a year in the style of Basquiat, Schnable, and Anselm Kiefer, he sketched in notepads, address books, and folders reminiscent of Honore Daumier, but it wasn’t until he began painting impressionist and expressionist cityscapes, which professor Jose Orozco of Whittier College refers to as urban pastoralism, that people began to take notice. Mostly disillusioned, ignored, and losing hope because people were indifferent to the work he offered, he was encouraged in 1991 by Sister Karen at Self-Help Graphics to paint the cityscape barrios using watercolors and oil pastels to illustrate the colorful abstract skies, the dignity and vibrancy of the people amongst the landscapes, and the representational urban complexities expressed through cultural and civic pride. By the mid 2000’s, Roberto Gutierrez moved from colorful urban pastoralism to black and white landscapes often recalling an industrial-era feel and Kafkaesque nightmare of the barrios of Los Angeles that look like they could’ve been painted by a German expressionist or French impressionist, or a combination of both. The somber and monochromatic images represent a departure from the colorful and vibrant narratives that developed out of commonplace Chicano art, and as the artist views it, it is a way to recall the gritty texture of the cityscape that is supposed to represent concrete or cement as a direct contrast to glamorous undertones often promoted by boosters. Most of these paintings are devoid of people and are meant to produce a feeling of emptiness because they represent a Los Angeles that no longer exists. The lack of people metaphorically represents a generation of people that are also disappearing, people of his age, which is difficult for him to face. His new project is in collaboration with Studio 50 in Highland Park, a solo show with several works depicting the 6th street bridge that is set to be demolished because it has been declared faulty and unsafe to handle earthquakes. The 6th street bridge is one of the most iconic symbols of Los Angeles, but often neglected, abandoned, disdained, and ignored, but it stands over the concrete and decay of the L. River like a character out of Fritz Lang’s. Looking down on the populace with authoritative observance. Currently Roberto has several watercolor paintings and canvases that observe the bridge from different perspectives, and the one I was most astonished by was the one painted in black and white, with a dreary blue sky that is sobbing for the bridge that will no longer exist. I knew then that I was no longer looking at a painting of a bridge.